Let no soul think

my vows of vengeance

will rest

within mere lines of poetry.

With heads held high

and honor unbroken,

we walk toward the noose

that swings in the square —

not with tears,

not with trembling,

but with prayers that rise

like smoke

to the sky.

Let the mothers not weep,

let the children not cry —

our silence

is not surrender,

but a return

to the Divine.

In our love,

there is no room for mourning.

Wait for the spring —

watch for it!

Even if we fall,

our song will remain.

I lived

A shadow fell

in the prime of my days

when the sun

was suddenly eclipsed.

across my country.

I sent thousands

of brave ones to the front —

and in one breath of history,

gave a thousand martyrs.

While those responsible

cowered

in their quiet corners.

But in our love,

there is no room for fear.

Look to fate —

but watch for victory.

Even if we die,

our song will remain.

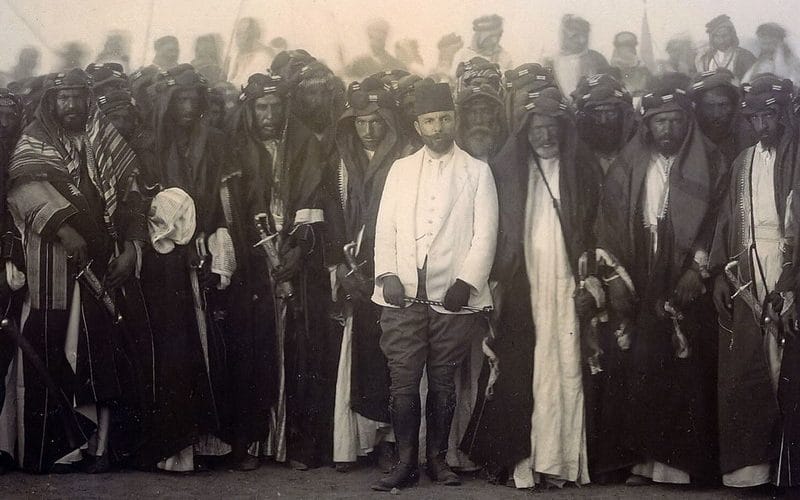

The Falcon of the Altai (c. 1889/1899–1951)

Osman Batur stands among the last great steppe commanders of the modern age—an Altai Kazakh horseman who forged a guerrilla army in the mountains of Eastern Turkistan and held off empires armed with tanks and aircraft. To his followers he was not merely a chieftain but a living standard of defiance; to his enemies, the uncatchable shadow moving ridge to ridge. He fought, lost, fought again, and died unbent—leaving behind a tradition rather than a throne.

I may give my life, but as long as the world turns my nation will continue the struggle.

Attributed final words of Osman Batur, Ürümchi, 29 April 1951

A frontier childhood

Born to the family of İslâm Bey and Ayça (Kayşa) Hanım in the Köktogay (Koktogai) district of the Altai, Osman grew up inside the seasonal rhythms of Kazakh nomadism: horses, pasture, and the rifle. By ten he was a fearless rider and a capable hunter. His military schooling began in earnest when the famed guerrilla leader Böke (Boko) Batur recognized his promise and taught him the craft of irregular war—ambush, mobility, and discipline—as well as a hard, enduring mistrust of Russian and Chinese power on the frontier.

“Today they take our guns…”

By 1940, abuse, desecration of mosques, and weapons seizures radicalized many in Altai. When local authorities demanded all arms be surrendered, Osman delivered a line that would echo through his legend: “Those who take our guns today will take our lives tomorrow. If they want my rifle, let them come and take it.” He went “to the mountain”—the Turkic idiom for rebellion—and within days friends, kinsmen, and seasoned riders joined him: Süleyman, Nurgocay (Nurgocai) Batur, Kaseyin Batır, and others. From that nucleus grew a mobile force that bled garrisons with sudden strikes, then vanished into stone and snow.

Osman’s marksmanship became campfire lore. Riders swore he could pick out enemy officers at full gallop with a light machine gun braced at the hip. More important than his aim was his ethos: he ate the same food, rode the same distances, and shared the same risks as his men. He was austere, proud, and suspicious—yet relentlessly fair.

The Altai made free (1941–1944)

Between the autumn of 1941 and July 1943, Osman’s fighters turned scattered resistance into a campaign. On 22 July 1943, after a string of victories, the Altai was largely cleared of Chinese forces. In Bulgun, tribal and religious leaders bestowed on him the title “Han” and the honorific “Batur” (“hero; valiant”), formalizing a reality already felt in the valleys: Osman commanded the field.

With the Second World War still raging, the politics of Eastern Turkistan (Xinjiang) grew tangled—Soviet advisers, Mongolian intermediaries, local factions, and Chinese authorities all pressing their advantages. Through this maze Osman kept a simple line: fight for the land and the people first; bargain only to preserve both. By 1944–45, the liberation wave rolled beyond the Altai into the Kazakh districts north of the Tianshan, where several towns and wide tracts changed hands.

Power, partners, and peril (1945–1949)

Victory forced politics. Osman accepted civil and military posts—Altai Governor (Vali) and senior commander within the emergent coalitions that governed “Three Districts” (İli/Kulca, Altai, Tarbagatai). Alliances shifted as Soviet influence waxed and waned and as rival leaders weighed independence dreams against survival.

Chinese reprisals were personal and brutal—family members were imprisoned or murdered; children thrown into wells, a cruelty remembered in folk laments. Osman answered by reorganizing for long war: lighter columns, deeper mountain bases, tighter intelligence. Yet the tide was turning. In 1949, with the Communist victory on the mainland, increasingly modern, numerous forces pressed into every valley. Osman refused surrender; he reduced his footprint and prepared for the last campaign.

The last ride (1950–1951)

By late 1950 the force that once numbered tens of thousands (including auxiliaries and camp followers) had dwindled to a few thousand souls, women and children among them. Osman’s bands slipped between Makai and Kayız, living on nerve and snowmelt. In February 1951, after a running fight in a mountain pass, he was captured—reportedly only after expending his last cartridges while rescuing his teenage daughter from a pursuing detachment.

Dragged first to Dunhuang and then to Ürümchi, he endured public humiliation and heavy torture but no confession. A show trial delivered the expected verdict. On 29 April 1951, he was executed by firing squad. Witness accounts agree on his composure and on the message he shouted to the crowds: the man could be killed; the cause could not.

How he fought—and why it mattered

- Guerrilla mastery: Osman turned the Altai’s geography into a weapon—short, violent actions; strict march discipline; elastic, multi-directional retreats that lured columns into empty country.

- Moral economy of command: He shared hardship, punished theft and abuse, and kept spoils tightly controlled—key to maintaining civilian support in a war of proximity.

- Symbolic clarity: Titles like Han and Batur were not vanity; they condensed legitimacy into words ordinary herders could trust. He embodied a simple contract: I will not leave the mountains before you are safe—or I am dead.

Character and presence

Physically imposing—about 1.85 m, broad-shouldered, with half-lidded eyes and a terse manner—Osman projected force without theatrics. Those who served with him describe a man of few words, a permanent furrow between the brows, and a temperament tempered by both kudret (native power) and kötü talih (ill fortune). He allowed himself no private ambition beyond the “great aim”: to begin from the Altai and, as in the age of Chinggis, drive foreign power from Turkic lands.

Legacy

To Kazakhs and Uyghurs of Eastern Turkistan, Osman Batur became not just a chapter but a vocabulary: resistance with a saddle under it, the right to worship without humiliation, the right to keep one’s rifle, the right to pasture in peace. Poems, memorial days, and oral histories keep his image alive—sometimes as a stern saint of the high country, sometimes as a frontier Šamīl, sometimes simply as Osman, the man who would not come down from the mountain on enemy terms.

For Codex Cumanicus, he belongs with those who turned defeat into instruction. Their victories are often temporary; their afterlife is long.

Osman Batur’s story reminds us that freedom movements need both ground (a place to stand) and grammar (a way to speak about justice). He gave his people both.

Legacy

Because history’s map is not only lines and treaties; it is also the memory of those who refused to bow. Osman Batur’s world was small in square kilometers and vast in meaning.

For any people confronting domination, his vow from the scaffold reads like a command to the living: stand, speak, ride—until the next rider takes your place.

Timeline

- c. 1889/1899 — Born in Öndirkara (Köktogay), Altai.

- Youth — Trains in irregular warfare under Böke/Boko Batur.

- 1940 — Refuses disarmament; takes to the mountains.

- Oct 1941 – Jul 1943 — Guerrilla campaign across the Altai.

- 22 Jul 1943 — Altai largely liberated; acclaimed Han and Batur at Bulgun.

- 1944–45 — Operations spread north of the Tianshan; assumes senior civil/military roles.

- 1946–49 — Fractious politics; renewed war; Communist advance.

- Aug 1950 – Feb 1951 — Final retreat toward Makai/Kayız; capture.

- 29 Apr 1951 — Executed in Ürümchi.

Further reading (selected)

- Godfrey Lias, Kazak Exodus (1956); tr. Göç (İstanbul, 1973).

- Hızır Bek Gayretullah, Altaylarda Kanlı Günler (1977).

- Christian Tyler, Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang (2003).

- Ömer Kul, On Yıla Sığan Efsanevi Ömür: Osman Batur Han (2010).

- TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi, “Osman Batur” (EK-2, 2019).