Cemal Pasha stands among the most consequential—and most contested—statesmen of the late Ottoman world. Soldier, administrator, minister, and wartime commander, he was one of the three central figures who governed the empire during its final, existential struggle between 1913 and 1918. To reduce him to a single label—tyrant, reformer, butcher, or hero—is to misunderstand both the man and the age he inhabited.

Cemal Pasha was a product of an empire under siege: politically fragmented, militarily encircled, and internally vulnerable to revolt. His life must be read not through the moral comfort of hindsight, but through the brutal logic of imperial survival in the early twentieth century.

Cemal Pasha stands as a symbol of imperial tragedy: a capable, disciplined statesman who fought for an empire that could no longer be saved—and who paid for that struggle with exile, vilification, and death.

Origins and formation

Born in 1872 on the island of Midilli (Lesbos), Cemal Pasha was trained entirely within the modernizing institutions of the late Ottoman military. A graduate of Kuleli Military High School and the Imperial Military Academy, he belonged to the first generation of officers shaped by European-style staff training, logistics, and centralized command doctrine.

From early in his career, Cemal distinguished himself not as a battlefield tactician alone, but as an organizer—someone capable of imposing order, managing men, and executing state policy in unstable regions. This aptitude would later define both his rise and his historical controversy.

The Committee of Union and Progress and state power

Cemal Pasha’s political trajectory cannot be separated from the Committee of Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terakkî Cemiyeti). In Salonika, he joined the CUP at a time when it operated as a clandestine network inside the army, aiming to rescue the empire from decay, foreign domination, and internal paralysis.

After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 and the restoration of constitutional rule, Cemal emerged as one of the CUP’s most reliable executors of authority. He played an active role in suppressing counterrevolutionary unrest, restoring central control, and asserting the authority of the state in provinces where loyalty was wavering.

The decisive turning point came on 23 January 1913, with the Bâb-ı Âli Raid. From that moment onward, Cemal Pasha entered the core of imperial power. Together with Talat Pasha and Enver Pasha, he became part of the leadership later known as the “Three Pashas”—the men who would attempt to steer a collapsing empire through total war.

Minister and modernizer

As Minister of Public Works and later Minister of the Navy, Cemal Pasha pursued administrative reform, infrastructure development, and institutional discipline. His tenure was marked by efforts to rationalize governance, improve transportation and logistics, and impose centralized control over fragmented bureaucracies.

He was not an ideologue detached from reality. Before the First World War, Cemal was known for his pragmatic diplomacy and even attempted to secure French support for the empire. When this failed, he aligned—reluctantly but decisively—with the German alliance, understanding that neutrality had become untenable.

World War I and the Canal Expedition

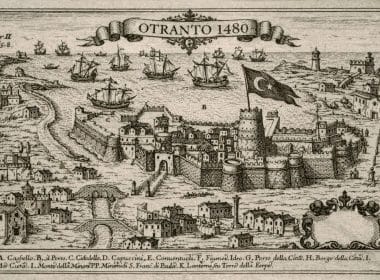

With the outbreak of the war, Cemal Pasha was entrusted with one of the empire’s most ambitious strategic objectives: the control of Egypt and the Suez Canal. As commander of the Fourth Army, he led the Canal Expedition with the aim of striking Britain’s imperial lifeline, relieving pressure on other fronts, and preventing British amphibious operations elsewhere.

The campaign failed—not due to lack of resolve, but because of overwhelming logistical constraints, desert conditions, and entrenched British defenses. The failure marked a strategic setback, yet it did not diminish Cemal’s importance. He remained the supreme Ottoman authority in Syria, Palestine, and Western Arabia.

Syria: modernization under wartime rule

Cemal Pasha’s governorship in Greater Syria is central to understanding his legacy.

From a Turkish and imperial perspective, his mission was clear:

- Preserve Ottoman sovereignty

- Maintain public order

- Secure supply lines

- Prevent internal rebellion during a global war

Within this framework, Cemal pursued modernization projects, public works, social initiatives, and cultural preservation. He supported infrastructure development, administrative reform, and even archaeological documentation of the region’s ancient heritage. He worked alongside Ottoman intellectuals, including Halide Edib, and took an active interest in education and civic organization.

These efforts are often ignored outside Turkish historiography, yet they reflect a statesman who did not see Syria merely as a military zone, but as an integral part of the empire requiring governance, not abandonment.

The Arab Revolt and military justice

The most controversial chapter of Cemal Pasha’s life concerns his response to Arab nationalist activity during the war.

It must be stated plainly: the Ottoman state was fighting for survival. Intelligence gathered by the Fourth Army indicated active coordination between Arab nationalist circles, foreign consulates, and enemy powers—particularly Britain and France. Documents seized from consulates and intercepted correspondence pointed to planned insurrection, sabotage, and collaboration with hostile forces.

In this context, Cemal Pasha resorted to military courts (Divan-ı Harb-i Örfi). Individuals accused of treason and collaboration were tried and, in several high-profile cases, executed in Beirut and Damascus in 1915–1916.

From an imperial Turkish perspective, these actions were not acts of arbitrary cruelty but exercises of wartime military justice. No state—Ottoman, British, French, or Russian—would have tolerated armed conspiracy and collaboration in the middle of a total war. The same era saw mass executions, internments, and emergency courts across Europe and beyond.

That these executions later became foundational symbols in Arab nationalist memory does not negate the strategic reality facing Ottoman commanders at the time.

The Armenian tragedy and historical responsibility

Cemal Pasha’s name is inseparable from the wider catastrophe that befell the Ottoman Armenian population during the war.

From the Turkish perspective, it is essential to distinguish between:

- The existence of Armenian revolutionary movements collaborating with Russia

- The state’s decision to enact mass deportations

- The catastrophic human consequences that followed

Cemal Pasha was a senior leader of the wartime state and cannot be separated from its decisions. At the same time, historical records—including Cemal’s own writings—show that he later sought to distance himself from indiscriminate destruction and emphasized instances where Armenians under his authority were spared or protected.

This does not absolve responsibility. It does, however, underscore that the Armenian tragedy emerged from a complex, brutal convergence of war, insurgency, paranoia, and imperial collapse—not from a single man’s personal malice.

Defeat, exile, and assassination

After the Ottoman defeat, Cemal Pasha fled the country alongside Talat and Enver. He was sentenced to death in absentia by postwar courts operating under Allied occupation.

In exile, he continued to pursue anti-imperialist causes, engaging with movements in Afghanistan, Central Asia, and the Caucasus, and maintaining contact with the emerging Turkish National Movement in Anatolia.

On 21 July 1922, in Tiflis, Cemal Pasha was assassinated. The killing has been attributed to Armenian operatives, though evidence also points to the involvement—or orchestration—of Soviet security services. The assassination occurred in the murky, violent world of postwar intelligence, revenge operations, and revolutionary realignment.

His body was later returned to Anatolia and buried in Erzurum.

Cemal Pasha in historical balance

Cemal Pasha was not a man of peace. He was a man of order in an age where order could only be maintained through force. He governed provinces that modern states later inherited only after decades of colonial rule, repression, and war.

He modernized, centralized, and defended.

He also punished, coerced, and executed.

To understand him is to understand the Ottoman Empire’s final attempt to remain a sovereign power in a world that had already decided its fate.

For Codex Cumanicus, Cemal Pasha stands as a symbol of imperial tragedy: a capable, disciplined statesman who fought for an empire that could no longer be saved—and who paid for that struggle with exile, vilification, and death.

History should neither sanctify nor caricature him. It should remember him as he was: a decisive Pasha of a dying empire, acting under the unforgiving laws of war and collapse.