In Catholic memory, Otranto is not first remembered as a port, a fortress, or a frontier.

It is remembered as a wound.

European and ecclesiastical sources; especially those written in the decades and centuries that followed—cast the Ottoman landing of 1480 as a moment when Islam stood at the threshold of Christendom. The fall of the city was narrated not merely as a military event, but as a theological rupture: churches profaned, relics scattered, and the refusal of local inhabitants to convert later sanctified as martyrdom.

In this tradition, the Ottomans appear less as a state than as an abstraction;

the Turk, the infidel, the crescent at the gate.

These accounts were not written to explain strategy or logistics.

They were written to warn, to remember, and to bind identity through suffering.

Otranto became a symbol precisely because it did not last.

Yet memory is never neutral.

And what Europe remembered as an existential threat, the Ottoman world experienced as a measured extension of imperial logic, shaped by geography, trade, and inheritance.

This is not a story of inevitability, but of approach.

Not of triumph, but of proximity.

Not of Rome taken, but of Rome imagined.

II. The Event Itself: A Chronological and Factual Account

The Landing and Siege (July–August 1480)

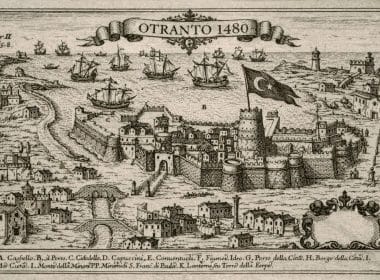

In late July 1480, an Ottoman expeditionary force under Gedik Ahmed Pasha crossed from the Albanian coast and landed near Otranto.

Modern estimates, based on Italian and Ottoman-aligned sources, place the force at approximately:

- 15,000–18,000 troops

- Supported by 90–120 ships, including transport and war galleys

Otranto itself was lightly defended. Its fortifications were outdated, its garrison small, and external assistance absent. After a brief resistance, the city fell on 11 August 1480.

The Aftermath

Following the capture:

- A significant portion of the population was killed or enslaved

- Churches were damaged or repurposed

- Surviving elites were ransomed where possible

The number “800 martyrs” belongs to later Catholic tradition; contemporary sources vary widely and do not provide a single, fixed figure. What is historically secure is that executions occurred, and that refusal to convert became central to later Christian memory.

The Ottoman Occupation (1480–1481)

The Ottomans held Otranto for roughly 13 months.

Crucially:

- The occupation was limited, not expansive

- No large inland conquest followed

- Raids occurred, but no sustained Italian campaign materialized

This was not an invasion of Italy in the modern sense, but a forward bridgehead — precarious, exposed, and dependent on wider imperial conditions.

The End of the Occupation (1481)

In May 1481, Mehmed II died suddenly.

His death triggered:

- A succession crisis

- Strategic uncertainty

- Immediate reassessment of western operations

By September 1481, Neapolitan and allied forces reoccupied Otranto. The Ottoman garrison surrendered under negotiated terms and withdrew.

The Italian reconquest was real — but it succeeded largely because the Ottoman project had lost its center.

III. Why Otranto? Ottoman Strategy after Constantinople

After 1453, Mehmed II did not merely conquer a city — he claimed an inheritance.

In Byzantine and Islamic sources alike, he was styled:

- Kayser-i Rûm — Caesar of Rome

- Heir to imperial universality, not a regional sultan

From this perspective, the Mediterranean was not a frontier, but a continuum. Control of sea lanes, ports, and trade arteries was essential to imperial legitimacy.

Ottoman strategy in the west had already demonstrated this logic:

- Albania secured as a launch point

- Pressure applied to Venetian holdings

- Rhodes targeted as a naval obstacle (besieged in 1480, unsuccessfully)

Otranto fit this pattern:

- A crossing point between Balkans and Italy

- A symbolic foothold on former Roman soil

- A naval outpost, not yet a province

It was, strategically, an opening move, not a conclusion.

IV. Venice, Diplomacy, and the Question of Encouragement

Ottoman–Venetian relations in the second half of the fifteenth century cannot be understood as neutral diplomacy. They were transactional, calculated, and frequently duplicitous.

Turkish historiography – drawing on Namık Kemal and Hammer-Purgstall – preserves a clear and consistent assertion: that Venice, having temporarily secured itself against Ottoman power, deliberately redirected that power toward southern Italy, with the specific aim of weakening the Kingdom of Naples.

At the time, Venice was engaged in conflict with Spain and its allies. Naples, openly supported the Spanish crown. To Venice, Naples represented not only a rival but an obstacle in the balance of Mediterranean power.

It was in this context that Venice dispatched an envoy to Istanbul.

According to Turkish historical accounts, this envoy argued before Sultan Mehmed II that the great cities of Apulia and Calabria had been founded and shaped by Greeks, as lands of the Eastern Roman world. Since the Sultan had already conquered Constantinople and assumed the title Kayser-i Rûm, it followed; both legally and symbolically, that these former Roman lands lay within his rightful imperial horizon.

This reasoning was not alien to the political logic of the fifteenth century. Empires advanced claims not merely by arms, but by inheritance.

The Venetian envoy identified in this tradition is Andrea Gritti, at the time an experienced bailo in Ottoman domains, deeply familiar with court politics in Istanbul. Gritti was no marginal figure. He was a seasoned merchant-diplomat, later Doge of Venice, whose survival from imprisonment on espionage charges already testified to his proximity to Ottoman power.

That Venice sought to divert Ottoman pressure away from its own territories, while encouraging action against Naples, is beyond serious dispute. Venetian intelligence networks monitored southern Italy closely, and Venetian diplomacy consistently sought to manipulate the direction of Ottoman expansion.

Venice benefited from Ottoman action against Naples, encouraged a legal–historical justification for it, and raised no objection when it occurred. Thus, Venice cannot be described simply as a passive observer. Nor can it be absolved as an uninvolved bystander.

V. An Almost-Conquest

Otranto was not the beginning of an Italian province.

Nor was it a mere raid.

It was something rarer in history:

an almost-conquest.

Had Mehmed II lived longer;

had a coordinated fleet moved faster;

had Italy remained divided —

the Adriatic might have become an Ottoman lake.

But history turns on contingencies, not intentions.

The Ottomans reached Italy – briefly, deliberately, and decisively – and then withdrew, not in defeat, but in recalibration.

VI. Closing Reflection

This account does not deny Christian suffering. Nor does it sanctify Ottoman arms.

It restores scale, context, and voice.

Otranto was not the end of Christendom, nor the failure of the Ottomans. It was a moment when empire touched empire and then passed.

The Turkish voice remembers it not as triumph, but as presence.

References

- Namık Kemal, Osmanlı Tarihi, Vol. II, pp. 315–316, İstanbul

- J. von Hammer-Purgstall, History of the Ottoman Empire, Vol. I

- Gaetano Conte, “Una flotta siciliana ad Otranto (1480)”, Archivio Storico Pugliese, LXVII (2014)

- Giuseppe Orlando D’Urso, “Il Castello di Corigliano fu assediato dai Turchi?”, Note di Storia e Cultura Salentina (2010–2011)

- Giovanni Albino, De bello Hydruntino (1495)

- Contemporary Neapolitan and Venetian correspondence (as cited in Conte)